By Habjon Hasani

Intro:

This long-form info-analysis attempts to explore the circumstances and motives behind the arrests of key (former) executives of the Bankers Petroleum corporation. The article is structured into two chapters. The first examines the criminal case file at the Fier District Prosecution Office, while the second ventures into a deeper inquiry into the hidden motives behind the current developments.

Chapter 1: The Ground Boils in Fier

Around 2010, when the Energy sector was under the command of Ilir Meta and the Socialist Movement for Integration (LSI), a convoy of five SUVs stopped in front of the “Sky Tower” in Tirana. The convoy belonged to a so-called “strongman” from Fier. He was waiting for businessman Rezart Taçi to come down from his office. They were rivals, competing over a tender for approximately 70,000 tons of oil that Albpetrol had put out to auction. This was oil that Albpetrol received through a production-sharing agreement with Bankers Petroleum.

At the time, the main bidders were Rezart Taçi—perceived to be connected to then-Prime Minister Sali Berisha—and a local group operating on behalf of the Energy Minister Ilir Meta. The convoy was not there to fight—it came only to deliver a direct message:

“You might win the tender. But you won’t enjoy it—you won’t set foot in Fier.”

Political negotiators soon got involved, and eventually the local group was awarded the highly-contested tender. That moment perhaps marked one of the clearest signals of the hydrocarbon sector’s decay. What was once the pride of Fier’s engineering and managerial elite had begun operating with the same mentality as the heroin trade—brutal, cynical, and utterly degenerate.

But the farce didn’t end there. The “icing on the cake” came shortly after.

Following the group’s victory, a celebratory dinner (grilled meat in clay pots, of course) was organized—not just with operatives and lieutenants in attendance, but also the local prosecutor of Fier, a senior judge, local political figures, and directors. At the start of the feast, the ringleader gave a short toast, with a hint of street jargon:

“We’ve been fools. We’ve risked our asses with drugs all over Europe chasing paradise. Paradise has been right beneath our feet all along—and we didn’t even know it. Cheers.”

“Cheers, enjoy it,” responded the prosecutor, the judge, and the political figures in unison.

Fifteen years later, little has changed in the climate and mentality of the city’s elite. Thus, it’s hard to believe that a criminal investigation into Bankers Petroleum could originate from the initiative of a junior prosecutor with just three years of experience, or a rookie judge. Logic dictates that this case file has powerful patrons behind it—well beyond the local scale.

Hashtag.al has reviewed the full prosecution file, including phone transcripts and annexes. The investigation began rapidly in February 2025. By March, wiretaps were authorized—right at the peak of the electoral campaign. Meanwhile,

Minister Belinda Balluku, the ruling party’s political enforcer, had already moved to Fier, compiling a list of every business with significant employment and budgets—to be “mobilized” for campaign support.

The initial lead for prosecutors came from the General Director of Taxation, a former prosecutor himself and a protégé of Ms. Balluku.

A deep dive into the file reveals the following core elements:

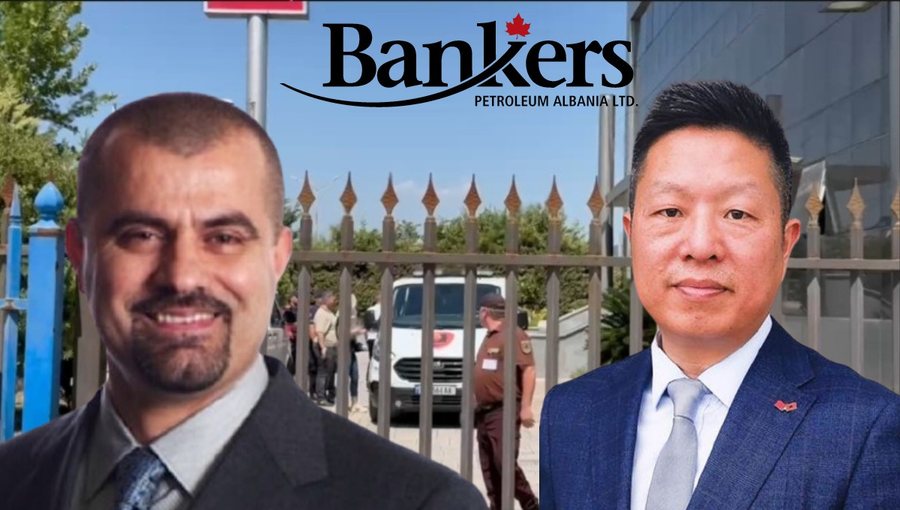

1.Leonidha Çobo, former director of Bankers, is accused of favoring a company called TEA&CO, owned by his sister-in-law, through inflated subcontracting deals. He appears in phone conversations with CFO Ardit Kero in March 2025, where banking matters are discussed. The conversations suggest that the two may have been conducting indirect business. However, the file fails to demonstrate how any laws were broken. Doing business, after all, is not a crime—it’s a goal.

2.CEO Xingyu Sun (China) is said to have fabricated invoices from shell companies to inflate costs and commit fraud.

3.Several legal or consulting firms—headed by Alket Hyseni, Eduart Halimi, and Besnik Çerekja—are accused of receiving substantial payments for allegedly fictitious services.

4.Wiretaps include conversations within the Bankers Petroleum finance and marketing departments, where staff are heard negotiating ad placements and influence with TV Klan and Top Channel. The file never explains what crime this might constitute. Still, Lori Hoxha, owner of Top Channel, is directly mentioned by name (by Bankers staff), while the prosecutor “can’t recall” the name of the Klan TV owner. This inclusion of both TV entities in the criminal file seems to function as a coded warning—a signal for these outlets to stay away from the story. Classic intimidation by inclusion.

Wiretaps seem to be the only concrete step taken by prosecutors, while the rest of the case appears to have been compiled—loosely—by the tax authorities. At least, as far as anything here can be called “compiled.”

The case’s underlying logic is overwhelmingly fiscal, not legal. It rests on the assumption that Leonidha Çobo subcontracted TEA&CO—a company run by his in-laws—for several hydrocarbon operations. And since the firm was run by family members, fiscal inspectors have classified it as a fraudulent and corrupt scheme.

But this claim comes with multiple problems:

– Leonidha Çobo had already been accused of this by the Chinese shareholders years ago—and he won the case in every court in Albania.

– The same allegations were even raised by the Albanian state in international arbitration, but the ruling exposed some crucial details.

First, the arbitral tribunal found that subcontracting required board approval, and unless it could be proven that the project was compromised, there could be no de jure or de facto conflict of interest between two private parties.

More importantly, the tribunal uncovered a clause in the hydrocarbon agreement that mandated Albpetrol to have a permanent representative scanning all subcontractors, with the explicit right of veto.

However, the arbitration ruling states in black and white that Albpetrol voluntarily waived this veto power, by never sending its representative.

And that alone is enough to render the matter non-justiciable—not even fit for judicial review.

Nevertheless, the case file is constructed as if none of this context exists. It operates entirely through Excel logic—numbers, charts, invoices—completely ignoring both domestic court decisions and the legally binding arbitration ruling.

The absurdity reaches its peak when prosecutors flag Leonidha Çobo’s salary as suspiciously high. But at no point does the file explain:

– Was Çobo’s salary higher than that of the American CEO before him?

– Is there a legal framework that defines what a CEO of a hydrocarbon corporation should earn?

– Where is this cap defined? In which contract or legislation?

– Are there any comparisons made with other CEOs in Southeast Europe?

A tax inspector, it seems, simply scribbled in the case file:

“I don’t like Loni’s salary.”

Maybe he found it high compared to his own.

A pretty bold legal theory to send a man to jail.

This fiscalist mindset continues with the naming of law firms like Alket Hyseni’s, Eduart Halimi’s, and Besnik Çerekja’s. The file highlights millions of dollars in fees collected over decades. Pro-government media focus on Halimi and Çerekja; opposition outlets attack Hyseni. Everyone gets a piece.

But there’s a fundamental problem here. These are not just legal services—they are also strategic consulting contracts. And in the world of international contracts, consulting doesn’t just mean periodic reports and Excel spreadsheets. It means influence. Access.

This is not something a tax inspector can measure—nor a district prosecutor, nor even SPAK.

Let me simplify it with a few examples:

What is the dollar value of a lawyer whose reputation is trusted by the Chief of Staff of the Arbitral Tribunal?

How do you price the credibility of a law firm that has direct access to justices at the Constitutional or Supreme Court?

Or let’s be more specific: what is the worth of Dorian Matlija’s personal contact in Strasbourg, who once got the European Court to freeze a media ruling in record time for Lapsi.al? Is that worth €1? Or €1 million?

How can a tax inspector assess the value of that? What do they know of such markets?

Let’s push it further. Imagine a strategic consultant from Albania flying to Zug, Switzerland. There, he is hosted in a villa or even a castle by his personal friend—a financial dynasty heir—joined by two trusted aides. The Albanian consultant requests access to connect a local businessman with:

– construction markets in Germany and Spain;

– energy opportunities in South Africa;

– and the inner circles of global fiduciary firms that manage the dynasty’s empire.

What’s the price of access to this kind of power?

A flight ticket to Switzerland with hotel and meals?

Seriously?

How on earth could a local tax inspector—or a district prosecutor—value that?

These people likely don’t even know such markets exist. They’re not trained to read those layers.

Because in these domains, the consultant sets his own value. He may tell the businessman:

“I want 50% of everything you earn through this new venture.”

Or he might say 20%. Or 7%. Or charge a hefty monthly fee.

There is no spreadsheet that can measure access to someone’s drawing room—especially when that someone doesn’t even receive Prime Minister Edi Rama in his house, only in his office.

These are the invisible economies of Western business logic, completely alien to Albania, where even hydrocarbon contracts are analyzed through the brain of a tax auditor who in February investigates Bankers, and by July is chasing dairy cans without receipts.

Chapter 2 – Who is Loni, really?

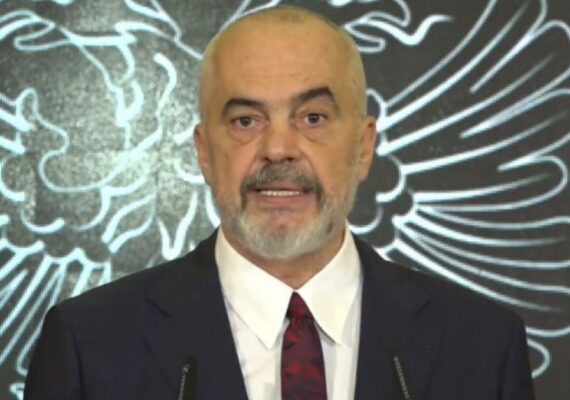

Around 2014, then-Energy Minister Damian Gjiknuri summoned two or three of his trusted people, handpicked for a mission directly authorized by Prime Minister Edi Rama.

“We want to know how much Bankers is really skimming. The Prime Minister wants the real figure, so we know where we stand,” Gjiknuri told them.

The specialists began work, and after several weeks they produced a confidential, informal report for Gjiknuri and Rama. Their conclusion: Bankers Petroleum was under-reporting by €54 million per year, rounded to €50 million, calculated retroactively from 2010. Earlier years had more ambiguous data due to inconsistent development plans.

When Leonidha Çobo learned of this estimate, he sent Gjiknuri a message:

“2010–2014 are five fiscal years. I agree to sign the contract now and pay €250 million immediately.”

Gjiknuri was thrilled. He went to Rama with the news, expecting praise. Instead, the Prime Minister looked him in the eye and replied bluntly:

“No.”

No one can definitively explain the Prime Minister’s sudden rejection, but the evidence suggests that several other things began happening immediately afterward.

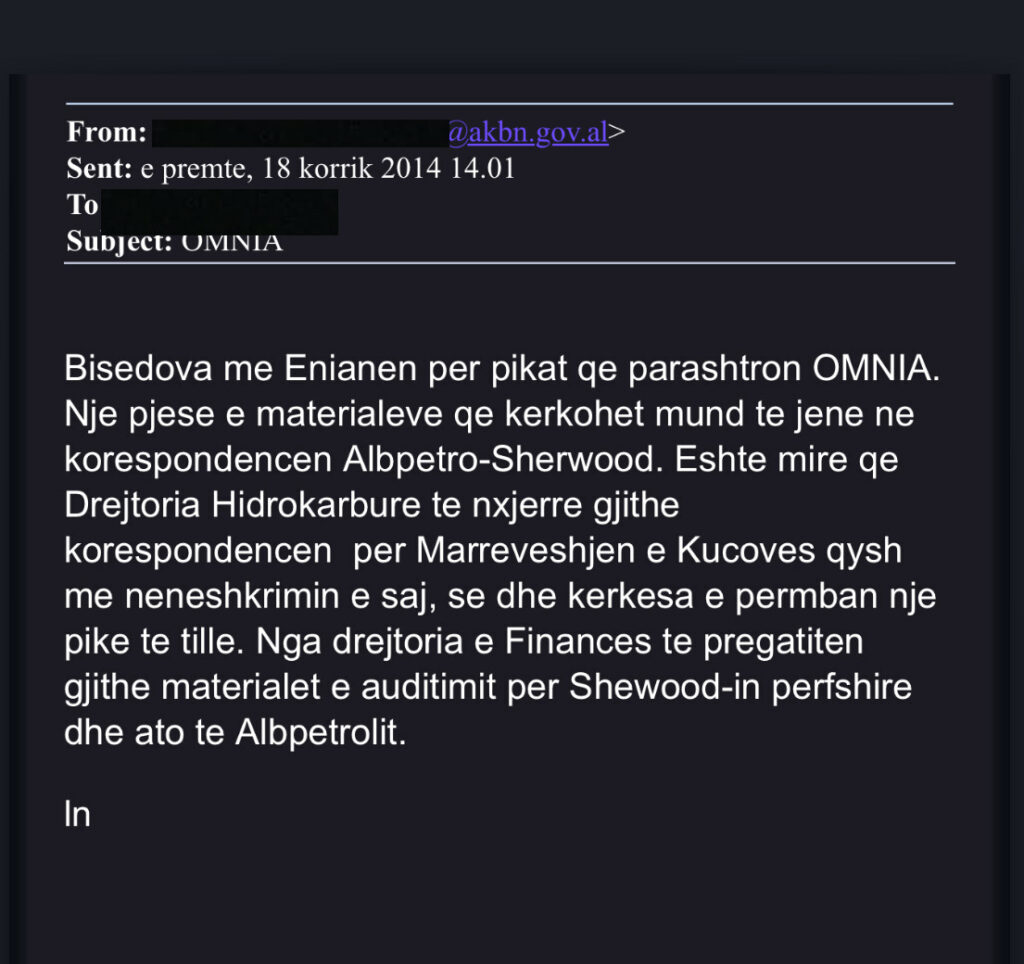

A cache of confidential emails—held by Hashtag.al for nearly a decade—suggests Rama may have seen the conflict with Bankers not as a threat, but as an opportunity to do some favors, both internationally and domestically.

For example, this email reads:

“Two senior figures from the hydrocarbons sector are effectively turning a state institution into a private department of OMNIA, after being tipped off that this company will be granted exclusive rights to represent Albania in arbitration against Bankers Petroleum.”

So, what is OMNIA?

It’s a company owned by Cherie Blair, wife of former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, a personal friend of Edi Rama.

This is just one tangent—an illustration of how favors were extended abroad after Çobo’s offer was rejected. But domestically, the game was also evolving.

Right around that time, relatives of senior Socialist Party figures began leasing public land in Fier. Coincidentally, these very plots were later included in Bankers’ development plans. The scheme was simple: lease land from the state for €7,000 per year, then sublease it to Bankers for €200,000 per year.

And so, Leonidha Çobo—the alleged “mobster”—had offered to pay €250 million into the state budget. But the “enlightened leadership” had other priorities:

– Offering contracts to Tony’s firm in London,

– And helping party insiders grab some quick profits from state land.

No one raises an eyebrow over the Berisha-Meta government in 2010 allowing heroin-trade logic into the hydrocarbons sector by involving underworld players.

No one flinches when Edi Rama’s administration channels money to Blair’s circle or when Socialist elites carve up land deals.

But Loni—he’s the problem.

He tried to pay €250 million into the budget.

And that, apparently, was his biggest mistake.

Now let’s ask: What does the Tax Directorate care about any of this?

What business is it of the prosecutor’s office?

How does any of this involve Tony Blair or Socialist land grabs?

To them, it’s all simple. Arrest Leonidha Çobo, build a case around some inflated invoices, and stir the public with moral outrage over his salary or his sister-in-law’s company.

And yet, the numbers suggest this government’s record with Bankers—and the hydrocarbon sector in general—is far worse.

By 2024, Bankers Petroleum had recorded $5.5 billion in total profits. Of that, they had paid only $550 million in royalties.

Even if we add Albpetrol’s share of pre-existing production, the figure reaches $700 million.

If we include social security contributions and other costs (which the arbitration didn’t fully recognize), the total contribution to the state budget is roughly $1 billion—around 20% of declared profits.

If we add indirect taxes paid by subcontractors (VAT, payroll taxes), the overall tax contribution rises to 25–30%.

But let’s say—just for argument’s sake—that Leonidha Çobo is a vampire, a mobster, a crook.

Here’s the real question:

What about those who get elected? Where do they stand in this story?

Let’s take Albpetrol, which receives a quota of crude oil from Bankers’ pre-existing wells.

Since 2010, Albpetrol has auctioned this oil at prices 30% to 50% lower than what Bankers would have paid directly at the wellhead.

In the Berisha-Meta era, some of this oil ended up with underworld figures.

Under Rama, things are more discreet—but still horrifically inefficient for the budget, and likely highly lucrative for insiders at Albpetrol and the Ministry.

Albpetrol has a contractual right to sell its quota directly to Bankers—at better prices than any fictitious auction can provide.

So why doesn’t it?

Why aren’t tax inspectors or prosecutors asking these basic questions?

They’re simple:

– Check how much oil was auctioned;

– Compare that to what Bankers would have paid directly;

– And calculate the difference.

We’re talking tens of millions of dollars in lost revenue.

Let’s now broaden the view.

Leonidha Çobo—despite all his supposed flaws—left behind a legacy in Fier.

Two of the city’s most prestigious companies today, AlbStar and Bolv-Oil, were created through Bankers’ subcontracting under Çobo’s leadership.

They’ve since diversified and made landmark investments across Albania.

So yes, this “vampire” left a footprint in the real economy.

Now ask yourself: What legacy has Minister Belinda Balluku left?

She appointed her personal family friend, Eltar Deda, as head of Albpetrol.

In eight years, Deda has produced no public results, no press conferences, no reports on management efficiency or investment. Nothing. Silence.

Meanwhile, Balluku may have also helped her protégé—now Director of Taxation—land his role.

In turn, he launched the pseudo-fiscal campaign that ended with Çobo’s arrest, ignoring arbitration rulings and global legal standards.

And here’s a final comparison:

What is the moral difference between Leonidha Çobo favoring his in-laws through a subcontract, and Balluku appointing her family friend to run a national oil company?

Yes, one is private, and the other is a public official. But which one was more efficient for the public budget?

Loni or Eltar?

The SPAK Dilemma

In recent days, pro-government media have screamed:

“Why hasn’t SPAK taken over this case?”

But these are the same outlets that once cheered SPAK when it arrested Thoma Gëllçi or Ilir Meta, only to scream in horror when Erion Veliaj was arrested.

They’re caught in the same psychological and moral trap.

Today, they hail SPAK. Tomorrow, they will vilify it.

Just like with Meta. Just like with Veliaj.

Besides, SPAK has proven one thing:

It burns big names for plane tickets and shopping receipts—not for high-level contract manipulation.

There is not a single SPAK case where a top politician has been prosecuted for international contractual corruption.

These are still cosmetic indictments, not structural accountability.

The fact that this case began in Fier brings comfort to both SPAK and the ruling party—it takes the heat off their own shoulders.

The story ends with a few fall guys.

Like “super-mobster Loni.”

But if this really is a hit job orchestrated by Balluku’s circle, what’s unclear is why Rama allowed it.

Especially given that Leonidha Çobo is deeply connected to the Kastrati Corporation, which Rama has embraced as a strategic partner for 12 years.

We are left with three conclusions:

– The case file is a fiscal hallucination, not a legal case—let alone one of international standard;

– It was likely constructed by a structure close to Balluku;

– And Rama may have greenlit it for reasons still undisclosed.

Perhaps he’s recalibrating his relationship with Kastrati.

Perhaps not.

But there’s one element they may have forgotten: the Chinese factor.

Rama and Balluku tried this playbook once before—with Fredi Beleri before the elections.

Today, Beleri is a Member of the European Parliament.

Meanwhile, Oltion Bistri (former Operations Chief), and prosecutor Aurel Zarka—both close to Balluku—were arrested shortly after, in cases gift-wrapped from Belgium.

It appears to be the same team. The same arrogant thinking.

The idea that states like Greece (let alone China) can be handled with the same logic:

“Give some contracts to Tony. Some land to our guys. Throw Loni in jail.”

Like they did with Beleri.

History suggests that Balluku-Rama arrests usually end up backfiring—sacrificing their own people in the end, especially if they cross red lines involving foreign powers.

And in this case, the foreign power is not just any power.

It’s China.

We may still be in the euphoric stage, like with Beleri.

But it’s far too early to tell how this story will unfold./Hashtag.al